“It’s like poetry, sort of. They rhyme.”

Sci-fi wonder boy turned fandom punching bag George Lucas said these words while describing the climax of his then-upcoming Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace, the long-awaited “next chapter” in the series that first made him Hollywood royalty and the idol of science-fantasy-loving dorks everywhere. Here, he’s comparing the final space-set dogfights of both the first and fourth – or fourth and first, if you want to get pedantic about chapter ordering in a series that started in the middle and went backwards – installments of the Star Wars saga. The twin stories of Anakin Skywalker, the father, and Luke Skywalker, the son – both boys raised on the sandy dunes of Tatooine dreaming of glory before being thrust into an intergalactic battle for balance in the metaphysical Force – are meant to mirror one another as only the most archetypal tales in the Joseph Campbell tradition can reflect.

The explanation George gives his crew regarding the storyboards for The Phantom Menace continues on, with the director attaching a possible more prescient statement at the end of his reflective aspirations: “Hopefully it’ll work.”

The twenty-year anniversary of The Phantom Menace came and went with little fanfare last May, the story of Qui-Gon Jinn and Obi-Wan Kenobi recruiting the midichlorian-riddled slave Anakin Skywalker into the stodgy Jedi Order receiving almost none of the attention that is usually afforded installments in the Star Wars canon. What was once the most highly anticipated movie of a decade has now become a footnote; an embarrassing blemish on the already spotty record of Star Wars films ever since the fuzzy, little band of Viet Cong analogs known as the Ewoks arrived in Return of the Jedi. So why has The Phantom Menace fallen by the wayside so much in the past two decades? What caused an entire online community to devote only a few token articles to its legacy when it was once the topic of intense debate from those within and without its generation-defining fandom? What has changed in the nature of “fandom” itself to leave The Phantom Menace as nothing more than a historical footnote in our franchise-obsessed New Millennium?

Star Wars has always been a children’s story, from its simplistic use of the “good vs. evil” narrative that’s been in vogue since Perseus set off to slay a Gorgon to dialog so corny Harrison Ford was once reported as joking to his director, “You can type this shit, but you sure can’t say it.” Love and war and betrayal and redemption are all binary concepts explored without significant nuance, if with more than a little bit of panache, wonder and heart than a thousand stories of its like that have failed to capture a crumb of the cultural cache as the original trilogy of films. But just because a story is childish, doesn’t mean it’s not worth celebrating as an adult. Parents don’t read their children fairytales because they fell obligated to uphold a tradition. They do it because there are foundational lessons in simple tales of heroes slaying villains and saving the innocent that stick with people throughout their lives. The problem with Star Wars has never been its inherent “childishness” – George himself maintains to this day that Star Wars is for “twelve-year-olds” – but in those who refuse to look for something beyond the first nostalgia-brewing feelings they received seeing the retroactively titled A New Hope in 1977, or whenever they first saw it or The Empire Strikes Back or Return of the Jedi.

Let’s step back to 1999, when The Phantom Menace was due to be released. Sixteen years had passed since Return of the Jedi, and up until then the idea of a Star Wars fan was split between two categories. The first was a person who was alive to experience Star Wars when it first hit the big screen and adopt it as a shifting force in the medium of film. The second was born into a world where Star Wars just…was. Compare this to children born after the release of Iron Man in 2008 and unaware that there was a world where the title character was a b-list at best superhero with a drinking problem and Robert Downey Junior was a failed actor with a drug problem. To that younger group Iron Man is the be-all, end-all of a-list superheroes – with his alcoholism toned down to a trendy functionality – and his actor is an icon known more for his quips and wearing of absurd goatees while living a clean and successful life. Fandoms can either discover a property or be born into it – and the trend seems to be heading more and more towards parents forcing their children to adopt their obsessions, to re-experience that initial thrill through a convenient cipher – and the way to delineate reactions to The Phantom Menace is to explore how a person came to experience it for the first time.

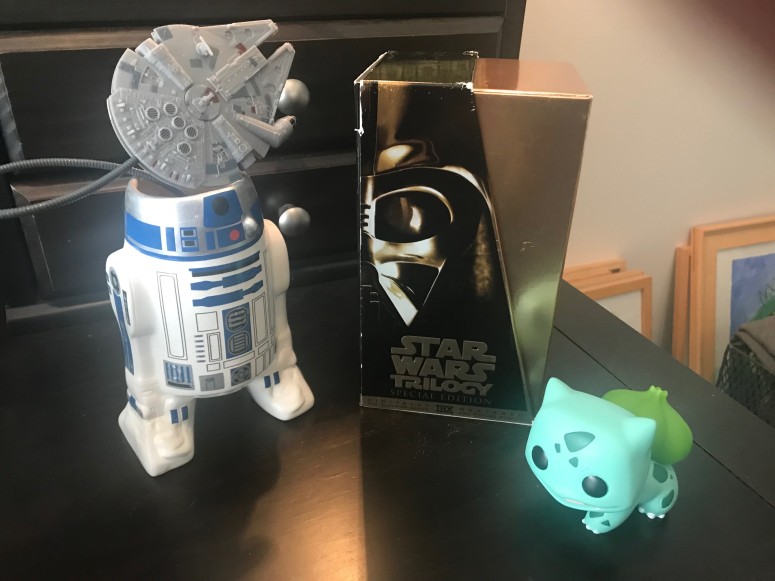

I was born into a world where Star Wars was more marketing juggernaut than film franchise. Though it had always been a source for the occasional action figure and recitation of “Luke, I am your father” into the back of a desk fan, I didn’t start embracing Star Wars until the release of the special edition VHS – impressive to my tactile-obsessed young mind in its glossy gold and black cardboard, cut to mirror the shape of Darth Vader’s helmet – that I found under the Christmas tree in December of 1997. The boxy tapes in hand, I slid the first cassette into my grandparents’ VCR with that familiar *ka-lunk* and sat back, taking only a second to absorb the silent “a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away…” before being bowled over by massive, yellow letters declaring STAR WARS and trumpeting into space on the notes of John Williams’s iconic opening fanfare. I’m not sure what moment completed the transition between “regular person” and “Star Wars fan,” but the images of droids bickering their way across the desert of a wookie blasting at Storm Troopers in an AT-ST or whatever the hell Yoda is whacking Luke across the head with a stick – I was always a sucker for the Muppets more than the people in the Star Wars universe, as I still am today – stuck with me and never let go.

I was a Star Wars fan in spirit, if not as a part of the community that had developed in the twenty years since its original release. Being ignorant to chat rooms and other internet-based sounding boards – my parents still years away from buying our first computer and insisting I write book reports on the electronic typewriter because it was “just as good with the electronics and stuff” – I wasn’t aware that George was “ruining my childhood” as so many fans came to complain regarding the changes made to the films through the special editions. The only version of Star Wars I knew had Han shooting in response to Greedo instead of getting to his blaster first and the scene at Jabba’s palace being stretched interminably by whatever the hell “Jedi Rocks” is – both of which are changes that I realize now are ill-advised at best, but this is about Carson: age seven. Age seven Carson didn’t care about directors going back to alter their original visions and possibly continue the despoiling of their art. I just knew there was an all-new Star Wars movie coming out and I was about to get more of what I had rapidly grown to love.

My wait between Star Wars films was roughly sixteen months long. Compare that to the sixteen years those who had come to Star Wars when it was still fresh had spent between the end of the original trilogy and start of the prequels. In the time between there were all sorts of expanded universe novels, role-playing scenarios and video games to drip-feed droplets of Skywalker goodness into the system of franchise fanatics, but nothing quite matches the grandeur of a big screen incarnation. In the time it takes to be ready for a driver’s license, Star Wars fans had been waiting to see how Anakin’s fall, the Clone Wars and the Empire’s rise all occurred. Sixteen years is a long time to formulate a plot in your head, and it can only lead to disappointment when things don’t line up. Just as everyone’s second favorite swamp-dwelling green Muppet once said, “there is no try.” The Phantom Menace could either be a perfect film fans had waited for or it could be a disappointment akin to Luke finding out his first kiss came from the only other prominent woman in the galaxy: his sister. There was no middle ground to be had in The Phantom Menace, regardless of intent on George’s part.

I have no memory of my immediate reaction to The Phantom Menace. I’m sure that since it had Artoo bleep-blorping his way across the screen and Jedi Knights doing backflips with laser swords that it more than satisfied my neon-eager nine-year-old brain on that balmy Monday evening my parents carted my sister and I to the nearby AMC. I’m sure even Jar Jar managed to score a few laughs from me in the “hey, that dumb alien just stepped in some space-shit that probably took three hundred hours of staging, sound work and animating so that George could be satisfied with the level of Gungan-to-Bantha-Poodoo-splatter-ratio he had squirreled away in a notebook thirty-five-years earlier” sort of way that just makes kids laugh. But I was a Johnny-come-lately to Star Wars fandom ready to move on to the next flashy thing on the big screen – Wild Wild West, most likely and most unfortunately. I wasn’t of the “before times” fandom. I wasn’t betrayed, as has become apparent to anyone willing to speak about The Phantom Menace in the following years.

You all know what happened next. Twenty years later and The Phantom Menace is synonymous with shattered expectations to the point where any articles mentioning the two-decade anniversary are inevitably about the fan betrayal that occurred in its wake. Entire documentaries have been made about the way in which people felt stabbed in the back by the special editions and prequels. This is the party line among the “before timers” in the fandom divide whenever anyone brings up The Phantom Menace. But there are outliers in the debate regarding The Phantom Menace’s quality. But there has been a new group of Star Wars fans to crop up since the prequel’s release. It had been seven years since Return of the Jedi was released the year I was born. Someone born seven years after The Phantom Menace’s release in 1999 would be nine when The Force Awakens – itself an attempt to recapture the thrills of the original film in the franchise – came out and is now a thirteen-year-old with about 1.7 million more Instagram subscribers than I’ll ever have. There is no longer just one type of Star Wars fan, since Star Wars has been around for so long and become so ubiquitous that multiple generations have embraced it in ways best suited to their own experience, like I did with the special editions. The divide can best be summed up by one scene in the criminally underwatched Spaced:

“The Phantom Menace sucked” is touted just as often as “The Phantom Menace is fine” just as often as “Star Wars always sucked” – though there’s no place for that latter group in this particular discussion – and on and on as fandoms grow older and once-derided properties become accepted for being worth enjoying on their own merits. Star Wars was a rallying point for fan unity, and as the franchise around which it grew swelled to Huttian-level proportions so did the types of fans within that fandom. Fan entitlement has always been an issue with pop culture properties, so why did it become such a flash-point in the two decades following The Phantom Menace? That, I’ve determined, has come with the rise of the Fandom Machine.

When I say “Fandom Machine,” I’m not talking about Transformers fans – thought that subset would come to have a significant role roughly eight years after The Phantom Menace’s release – but to the larger concept of Hollywood filmmaking revolving around fan-fueling I.P. so much that it has become the only form of measurable success in the two decades after the summer of ’99. There were certainly long-running franchises with their own fervent fandoms before Star Wars. You had the franchise’s cultural and ideological counterpart in Star Trek, which was up to nine films by the time The Phantom Menace was released. Marvel vs. DC had been two sides of the comic book shop civil wars since the ’60s, though the latter seemed to be doing far better than the former when comparing the mostly smash successes of Superman and Batman compared to the lone surprise hit – released after a string of failures like Howard the Duck, The Punisher and Captain America – that came in the form of the obscure vampire hunter Blade in 1998. And it’s not like James Bond and Godzilla could have both been at twenty-plus installments by the end of 1999 if they didn’t have fans willing to sit through the good and the bad as Bond switched actors and the Big-G got better at hiding that zipper at the back of his costume. Fandoms were certainly a thing in 1999, but they weren’t the thing.

Fans were still a joke as far as the larger populace was concerned. William Shatner had made a splash by shouting “GET A LIFE!” at Trekkies in an infamous Saturday Night Live sketch in 1986 and Galaxy Quest would take that concept to its extreme the same year The Phantom Menace was released by having its crew of washed up actors dealing with aliens that couldn’t separate fact from fiction in the “historical documents” intercepted from the original airing of its titular program. Even in the years following The Phantom Menace the larger concept of fandom would be a point of mockery, as Triumph the Insult Comic Dog’s interaction with Attack of the Clones fans on opening night would attest. Fandom-based film releases were still a niche affair – something only a small sect of the weirdo fanatics could get worked up about – and wouldn’t become EVENTS until the release of The Phantom Menace.

In the fifty years before The Phantom Menace’s release, only ten movies that won the worldwide box office in their release year – James Bond, Indiana Jones, Rocky, Terminator and Star Wars itself being the offending franchises – were sequels or later installments in a series. The rest were original works, Oscar winners and a boatload of animated Disney films that have definitely amassed their own fandoms over the course of eight decades. Ten out of fifty isn’t an irrelevant statistic, but it’s nothing compared to what came after.

In the twenty years since The Phantom Menace was released, every single film that won the box office the year in which it was released was either a sequel or the first installment in a franchise that would go on to have at least three sequels by 2019. Sure, you could claim that Avatar and Frozen were original properties and don’t count, but the former has four sequels in development right now and the latter has captivated an entire generation of children and locked their parents in a state of Disney Radio-induced Stockholm Syndrome thanks to endless renditions of “Let It Go.” When it came out, The Phantom Menace was a box office sensation no matter how middling the reviews, debuting right behind the “king of the world” meme-generating Titanic as number two all-time. Twenty years later, it sits at number thirty-five between the Time Burton/Johnny Depp fancy hat pageant Alice in Wonderland remake and the Finding Nemo sequel, Finding Dory: Ellen Needs a New Yacht So She Doesn’t Have to Swim with Any Real-Life Dorys.

Maybe that’s why The Phantom Menace has been so infrequently discussed as its twenty-year anniversary came and went. It isn’t considered a light switch that took us from a world where original, free-thinking Hollywood was populated by young Spielbergs, Scorseses and Lucases to a toyetic nostalgia-fest ruled by the Abramses, Snyders and Whedons of the modern age. Though the directors are still mostly white dudes. Maybe The Phantom Menace should be considered more of a dimmer that had slowly been cranking upwards as Star Wars went from “little sci-fi film that no one at Fox believed in” to “generation-shaping event” to “market-saturating merchandise generator.” Just as the fandoms need to be fed the original feeling they got wen Luke walked into a cantina on Mos Eilsey so too does the Fandom Machine need its fill of adaptations every year to sustain a box office that grows larger every year on inflated ticket prices while combating the onslaught of “Golden Age” television everyone’s been going on about for over a decade, with good reason. Everyone is a fan with a fandom now in the age of Pixar, Pirates of the Caribbean, the Marvel Cinematic Universe and even a few franchises Disney doesn’t yet own. If the Star Wars fandom fueled its box office domination even with most of its followers growing more dissatisfied with the product, surely every other property with a semblance of a following was worth adaptation regardless of quality.

Twenty years after its release and The Phantom Menace is a film with surprisingly similar resonance as the original Star Wars that preceded it by twenty-two years. It may not be for the breakthroughs in special effects – even though Jar Jar is an essential, if cringe-inducing precursor to the likes of Gollum, King Kong and anyone else Andy Serkis is playing in a skin-tight onesie this week – so much as for the reaction to the film itself. The Fandom Machine was once a creaky little tinker toy made to be mocked by the adults of the world more interested in biblical epics and family dramas at the theater. Now the machine has reached Unicron-like proportions, all because a single fandom spent sixteen years waiting for the perfect film to reignite past pleasures and Hollywood realized it no longer had to do more than find a following and slap an adaptation of their chosen passion on screen to rake in Scrooge McDuck pools of cash. The final film of the Skywalker saga – appropriately titled, The Rise of Skywalker – will come out this December, twenty years after the first infamous instance of Anakin Skywalker shouting “yippee!” and splitting a fandom in two. It’s likely the discourse surrounding this “final” film in the saga will be just as vociferous as that surrounding every movie these days, especially Star Wars films. But the Fandom Machine isn’t picky about the reaction to the reaction to gears and cogs that make up its greater workings so long as butts are in seats and hashtags are trending in the build-up to opening night. Surely, the reaction to The Rise of Skywalker will echo that of The Phantom Menace, in that childhoods will be ruined and legacies tarnished in retrospect. It’ll be like poetry sort of, they’ll rhyme. Though I doubt that’s what George meant when he first envisioned the symmetry between chapters in his saga when he first sketched them out a long time ago in a galaxy, you know the rest.

Next Time: The age of superheroes begins with a whole lot of black leather…

6 thoughts on “The Fandom Machine: Episode I – The Phantom Menace”